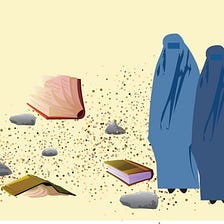

How the International Community Can Protect Afghan Women and Girls

Now that evacuations from Kabul’s airport have ended and the last foreign troops have gone, the focus shifts to the long-term human rights crisis in Afghanistan. The issue is what life will be like in Afghanistan—especially for women and girls—and what influence the international community will have. In an August 24 statement the G7 said: “We will work together, and with our allies and regional countries, through the UN, G20 and more widely, to bring the international community together to address the critical questions facing Afghanistan…

[T]he Taliban will be held accountable for their actions on preventing terrorism, on human rights those of women, girls and minorities and on pursuing an inclusive political settlement in Afghanistan. The legitimacy of any future government depends on the approach it now takes ….” This statement begs questions about what leverage the international community has, how it will use that leverage, how much cooperation there will be, what issues it will prioritize, and, of course, how susceptible the Taliban will be to pressure.

There is reason to worry that government donors will exhaust any leverage they have on conditions related to counterterrorism. But this is a key moment to consider what conditions and mechanisms could be most effective in trying to protect the rights of women and girls. The evacuation crisis may have delayed discussion by involved governments about these next steps. But Afghans do not have the luxury of time; a new crisis is rapidly unfolding, as most foreign aid to Afghanistan has been blocked. Because about 80 percent of the Afghan government’s budget comes from donors, the consequences were immediate—in the form of higher food prices, crowds outside banks, and warnings of an impending food shortage and collapse of the healthcare system.

Others, such as Nicholas Miller and Doug Rutzen and Adam Smith, have written about the urgent need to keep humanitarian aid and financial assistance flowing, and options to combine continued assistance with targeted sanctions and conditions.

Violence Against Women and Girls

Afghan women’s rights activists fought hard over the last 20 years for systems to respond to and protect women and girls from gender-based violence. They won important gains, including the 2009 Law on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and the creation of specialized courts and prosecution units. Donors supported these systems and services for survivors. While the system was poorly implemented, it still represented a fundamental change. That a woman or girl could flee violence and find safety and help, go to the police, testify in court, see her attacker punished, and start a new life with help from social services and lawyers helped to empower not just women and girls who used this system, but also others who knew the system existed.

A crucial question is what will happen to this hard-won system now, under Taliban control. It seems likely to be entirely disregarded and dismantled. Donors should press for, and monitor, detailed commitments from the Taliban about preventing forced and child marriage, and ensuring access to assistance and justice for women and girls facing violence in the home.

Heather Barr